What technologists can learn from the tragic Greek myth of Cassandra

Lately we’ve been inundated with news about how terrible technology is, and how “no one could have known” what awful outcomes would come from mixing humans and technology together. This blog post is a redux of a talk I gave in Vancouver recently, and it’s a hopeful (though a little stoic) analysis on how social scientists inside tech companies can stay the course, and keep talking about awful outcomes. If you’re just such a researcher, or maybe you’re a social scientist working outside tech companies, this post is for you.

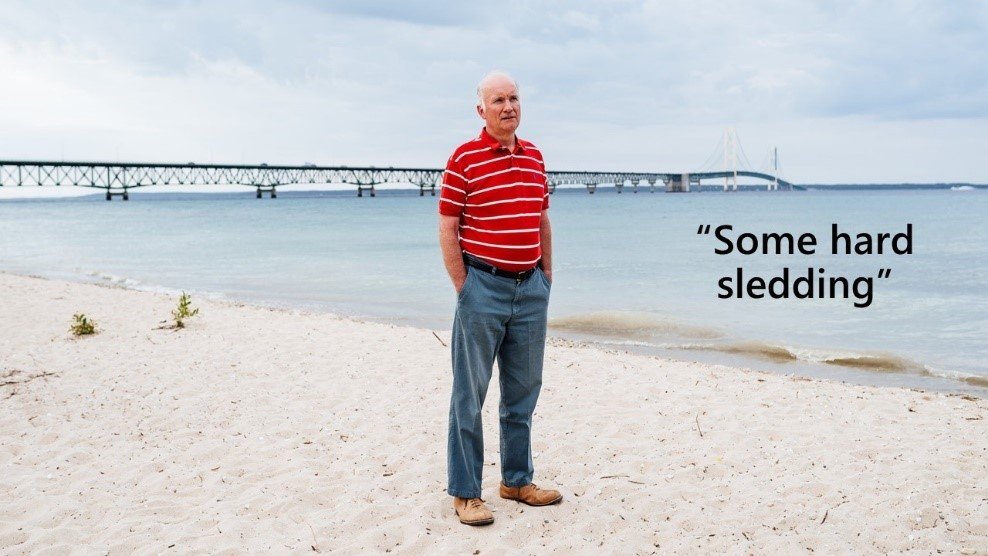

Tim Lee The New York Times

Social scientists inside tech companies might see a little of themselves in another social scientist, Tim Lee. Mr. Lee, a self-employed economist and works alone in an office in Greenwich, Connecticut.To make his living, Mr. Lee sells subscriptions to his newsletter called piEconomics to institutional and private investors – a boring, 10-page block of text analyzing, macro and microeconomic trends.

Back in 2011, the bearish Mr. Lee predicted a crash of the Turkish lira. Specifically, he said one dollar would buy 7.2 lira. Most people thought he was crazy. By 2018, Mr. Lee’s prediction came through. In August, the dollar bought 6.95 lira, and it may well his that 7.2 by year’s end. As you might expect, Mr. Lee was rewarded for his prescience…with cancelled subscriptions.

Wait, what?That’s right, his subscribers rewarded his accuracy and insight by taking back their money. Mr. Lee seems realistic about the whole affair. “It has been some hard sledding,” he told the New York Times. “I have lost a lot of clients because I am too bearish.”

People who do human-centred research inside a tech company know what Tim Lee feels like. These researchers have probably told people what they know to be true, only be disbelieved. Maybe there was a researcher inside Twitter that warned it would be a platform loved by Nazis. Maybe it was a researcher inside Facebook who warned the newsfeed is easily gamed for nefarious purposes. These researchers, just like Tim, both bearish, and probably both “rewarded” in the same way.

Social scientists inside tech companies, and Tim Lee, are a little like Cassandra, the tragic Greek hero who absolutely knew what sorrow was to come, yet no one believed her either. Social scientists inside tech companies, listen up: you can learn from Cassandra. A lot.

Cassandra in the Temple

When Cassandra of Troy was little, she and her brother camped out in the Temple of Apollo. While there, they had their ears licked by the temple snakes. This gave her the gift of prophecy. But Apollo being the vengeful Greek God we know him to be, also cursed her: she would see the future, but no one would ever believe her.In the beginning, she saw trivial things, like when visitors would arrive. But eventually, here visions became more grand, dramatic, and even scary.

It culminated in the mother of all warnings: Cassandra knew there were soldiers inside the Trojan Horse. And of course, no one believed her.Of course, Troy fell and the Trojans lost the war. She was kidnapped and enslaved by Agamemnon, of the winning side. When she got to Agamemnon’s palace, she got a terrible sense of foreboding. Sure enough, she was right: Agamemnon’s wife Clytemnestra murdered her and Agamemnon, and that was the end of Cassandra.

All the she ever did was tell the truth about what she saw, and accurately predict the future, and this is what she gets. A little bit worse than cancelled newsletter subscriptions, eh?Technology researchers know how she feels. They have real information that will help their technology partners do their jobs better. And yet, we often have this challenge: no one believes us.

That is some hard sledding. I mean, sure not-taken-as-a-slave-after-the-war-and-murdered-by-your-slaver’s-jealous-wife hard sledding, but you know, still kind of rough.What can we learn from Cassandra? This gift – her gift, our gift – comes at a cost. But it’s still a gift.

In fact, the fact that it comes with hard sledding is actually a blessing. But Cassandra didn’t understand that. The people of Troy really didn’t believe her, she got more and more hysterical. It was just this vicious circle. She didn’t embrace the cost of her gift.

The Cassandra Complex

Cassandra’s Warning of the Trojan Horse

Psychologist Laurie Layton Schapira writes about what she calls the Cassandra Complex, or the persistent experience of being unable to accept that others will not bow to your will. Schapira uses Cassandra to describe her patients who had become plaintive, immature whiny people who continually fail to move past the moment when people disbelieve them. Instead, they stay arrested in time, mired in pain, regret, and anger.

That anger is often justified; some of her patients had led very traumatic lives. The problem is that they stay angry, instead of reconciling and integrating that anger. They are unhappy, and stuck. They cannot move on with their lives.You can see how a researcher could fall into this same trap.

She might be literally saying, “My usability test predicted people will mistakenly post personal things” or “My ethnographic data clearly showed that the newsfeed is full of garbage.” But if you are not believed, over and over again, this begins to morph into “I am angry you do not believe me.”This is where Schapira finds her patients: caught up in the pain and anguish of not being believed. The Cassandra Complex is a real risk for researchers, either working within or even outside technology companies; we predict terrible outcomes and no one believes us. Eventually, they just stop listening.

I cannot tell you how many times I have been the one saying, “There are SOLDIERS in THAT HORSE!”

So how do you solve for the Cassandra Complex? I’ll start with what won’t solve it. First, self-care.

Look, self-care is bullshit. I’m sorry, it is. I’m not going to stop those soldiers from jumping out of the horse by reading a lot skin care advice from some rich white lady. No. It might give me nice skin, don’t get me wrong, but it won’t solve the problem. Sure, go ahead and get your 8 hours sleep, by all means, but that’s not what keeps Tim Lee alive during patches of hard sledding.

So forget self care. Do people fail to believe social science warnings because we are bad researchers? Also no. Decades of psychological research has shown that fixed minds are hungry for confirmation, not for refutation. Data can be valid and sound and still no one believes us, so it’s not the quality of the research.

No, wait, that’s not entirely true. Absolutely we can improve. We don’t spend enough time analyzing our data. We report a laundry list of “things that happened” instead of providing explanations of why they happened. We are fearful of making universal statements. We’re afraid of our voices, so we bury them. I quote here the Robert Solow, who says, “The fact that there is no such thing as perfect antisepsis does not mean one might as well do brain surgery in a sewer” (cited in Geertz, 2000). So just like self-care, being good researchers is necessary but not sufficient to solving the problem.

Why do people fail to believe when the evidence is clear? I gather data, as I’m trained to do, with the utmost rigor and care. I take pains to present the data in rigorous but also compelling ways. I encourage stakeholders to come along with me, to witness product failures first hand. I build relationships, and above all, I care. And yet I still fail. Why?

This phenomenon of not being believed is not about any individual but about the cultural context in which researchers practice their work. I like to believe it’s all about me but it’s not about me, or you, or Tim Lee, or even Cassandra. It is about the way we organize ourselves, as humans, into groups. It’s very difficult not to take things personally, but it helps if you understand that the context, which is not something you can control. Culture is, as Peter Drucker said, what eats strategy for breakfast.

Culture is what makes confirmation bias a generalized phenomenon; one person’s disbelief is confirmation bias, but a whole organization full of confirmation bias? That is culture. Humans need consensus for groups to stay cohesive and unfortunately, the nature of what we do attacks that consensus. The data we collect is what anthropologist Elizabeth Coulson calls, “uncomfortable knowledge” (as cited in Ramírez & Ravetz, 2011).

Technology researchers are the bearers of news, which can often mean bad news. It’s not about the individual researchers, but the hard role they are required to play. We are here to tell people things they don’t want to hear. It’s a hard job, and hard sledding is guaranteed. But it turns out, being the bearer of bad news is a unique and wonderful opportunity to become more self actualized, and lead a more meaningful life. It is the opportunity to be a hero.

All heroes must deal with failure. W.H. Auden wrote, “The typical Greek tragic situation is one in which whatever the hero does must be wrong” (Auden, 1948, p. 21 emphasis mine). So, you know, we are doomed. Sorry. We researchers are heroes, but more specifically, we are tragic heroes. Being Cassandra is actually a GIFT.

It is something that many people only dream about. It is the gift of self-creation. Sure, it’s foisted upon us, but it’s a wonderful gift. We know from philosophy that making oneself is the key to becoming a realized person.

Nietzsche wondered what makes a hero, and he found that it’s about integrate the best and the worst together: “What makes [us] heroic? To go to meet simultaneously one’s greatest sorrow and one’s greatest hope” (Nietzsche, 1977, p. 235). This is the path to a unique and truly meaningful life. Imagine if you lived your entire life without meeting your greatest sorrow. On the surface, it seems like a pretty good life, but it’s not. You cannot make sense out of goodness without badness. People whose job it is to point out the essential problems with their company’s products must face their sadness. But this is a gift.Simone de Beauvoir puts it bluntly. “Since we do not succeed in fleeing it, let us therefore try to look the truth in the face” (de Beauvoir, 1948, p. 24).

Let us embrace looking truth in the face. Facing your sorrow can be a path to reinvention. Polish Canadian psychologist Kazimierez Dabrowski has a wonderful way of thinking of meeting one’s greatest sorrow. He called it the theory of positive disintegration. Contrary to most psychologists, Dabrowski believed there was value in fear, anger, despair, and psychic pain because it can lead to a crisis, and then, ultimately, to growth. The key to this growth is taking advantage of psychic pain, making an opportunity to question yourself, your beliefs, and the gap between your ideal self and your current self.The key to weathering being a Cassandra is making peace with the gap between your ideal self and your actual self.

As Schapira tells us, "She needs to pull herself out of her with her own ego, finally to meet her own animus equal terms” (Schapira, 1988).

What does this mean? This means respecting that power you have inside you and embracing your masculine animus, or masculine power. Your animus is strong, confident, but can also be arrogant and aggressive. Cassandra is insightful and prescient, but she is plaintive and whiny. Imagine you integrate the two. Incorporate that power, don’t being afraid of it.We need to take a stand, be bold, and tell people when we disagree. At the same time, we must accept that we will probably fail. We must have courage in the face of this failure and instead of attaching ourselves to “success,” we should attach ourselves to the struggle.

This is how we become whole: by recognizing the struggle. There are some specific steps you can take to focus on the struggle, and meet your animus.To do this, researchers will need a daily dose of meaning. A lot of us believe meaning is something that exists out there, in the world, and our life’s task is to just find it.Meaning is not something you can find. Creativity coach Eric Maisel tells us that meaning is not something sitting on a shelf somewhere. It is something you must make, with the processes of your own mind.

“There are so many ways to kill off meaning: by not caring, by not choosing, by not besting demons, by not standing up” (Maisel, 2013, p. 129).

Incidentally, Maisel does endorse self care as well, but note that he too sees it as a enabler, not the outcome itself. “You will also have to change your life so that you feel less threatened, less anxious, less rageful, less upset with life, and less self-reproachful, and so on” (Maisel, 2013, p. 63).I keep asking myself, why didn’t Cassandra just go up to the horse and open the door!? Why didn’t she go all Arya Stark and just kill them all herself? Or at least die trying to kill them? What was WRONG with her? She let us all down, really.

So don’t be like Cassandra. Be more like Tim Lee. Tim Lee is now predicting a new crash, bigger than 2008, bigger than the Turkish lira. People don’t believe him, because of course.Courage, Sartre wrote, is the ability to act despite despair. So if you come in tomorrow and that same goddamn boulder is at the bottom of the hill, look at it. Think about its meaning. It your chance to be courageous. Tim Lee is still going. He’s had some hard sledding sure, but he’s also accepted that. And he has also said he stands by his predictions. So should you.

This post the full text of a presentation at the Radical Research Conference in beautiful Vancouver, British Columbia in September 2018.

References

Auden, W. H. (1948). Introduction. In W. H. Auden (Ed.), The Portable Greek Reader. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Bailey, F. G. (1983). The Tactical Uses of Passion: An Essay on Power, Reason, and Reality. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

de Beauvoir, S. (1948). The Ethics of Ambiguity. New York, NY: Open Road Integrated Media.

Geertz, C. (2000). The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Gilligan, C. (1993). In A Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Maisel, E. (2013). Why Smart People Hurt: A Guide for the Bright, the Sensitive, and the Creative. Red Wheel Weiser. Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=dJ1dQrbR-rkC

Mills, C. W. (1959). The Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press.Nietzsche, F. (1977). A Nietzsche Reader. London, UK: Penguin Classics.

October, T., Dizon, Z., Arnold, R., & Rosenberg, A. (2018). Characteristics of physician empathetic statements during pediatric intensive care conferences with family members: A qualitative study. JAMA Network Open, 1(3), e180351. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0351

Ramírez, R., & Ravetz, J. (2011). Feral Futures: Zen and Aesthetics. Futures, 43(4), 478–487. Retrieved from http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0016328710002880

Schapira, L. L. (1988). The Cassandra Complex: A Modern Perspective on Hysteria. Toronto, ON: Inner City Books.